The school and the ideology

The Bauhaus short-lived life between 1919 and 1933, is nowadays regarded as the school which shaped most of today’s knowledge of the modern and contemporary art and design world. Yet, it was regarded by Nazi Government as a promoter of Russian-Bolshevic idealisms, which made it to power following the October Revolution of 1917. These views by the Nazis, constituted the closing down of the school in 1933.

The school was aimed at raising questions about methods of teaching good art and design. Its founder, Walter Gropius planned to get all arts, including architecture under one roof and create mass produced design goods within all media. The Bauhaus had to be a pro-active space housing different point of views.

This was achieved by breaking away from the dichotomy in Weimar. The initial years, 1919-1923, saw the Bauhaus being influenced by Romantic idealisms, especially through the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement and its main protagonist and leader, William Morris. Yet, unlike this movement, the project promoted works which were industry-friendly and embraced the innovation brought by through the industrial revolution.

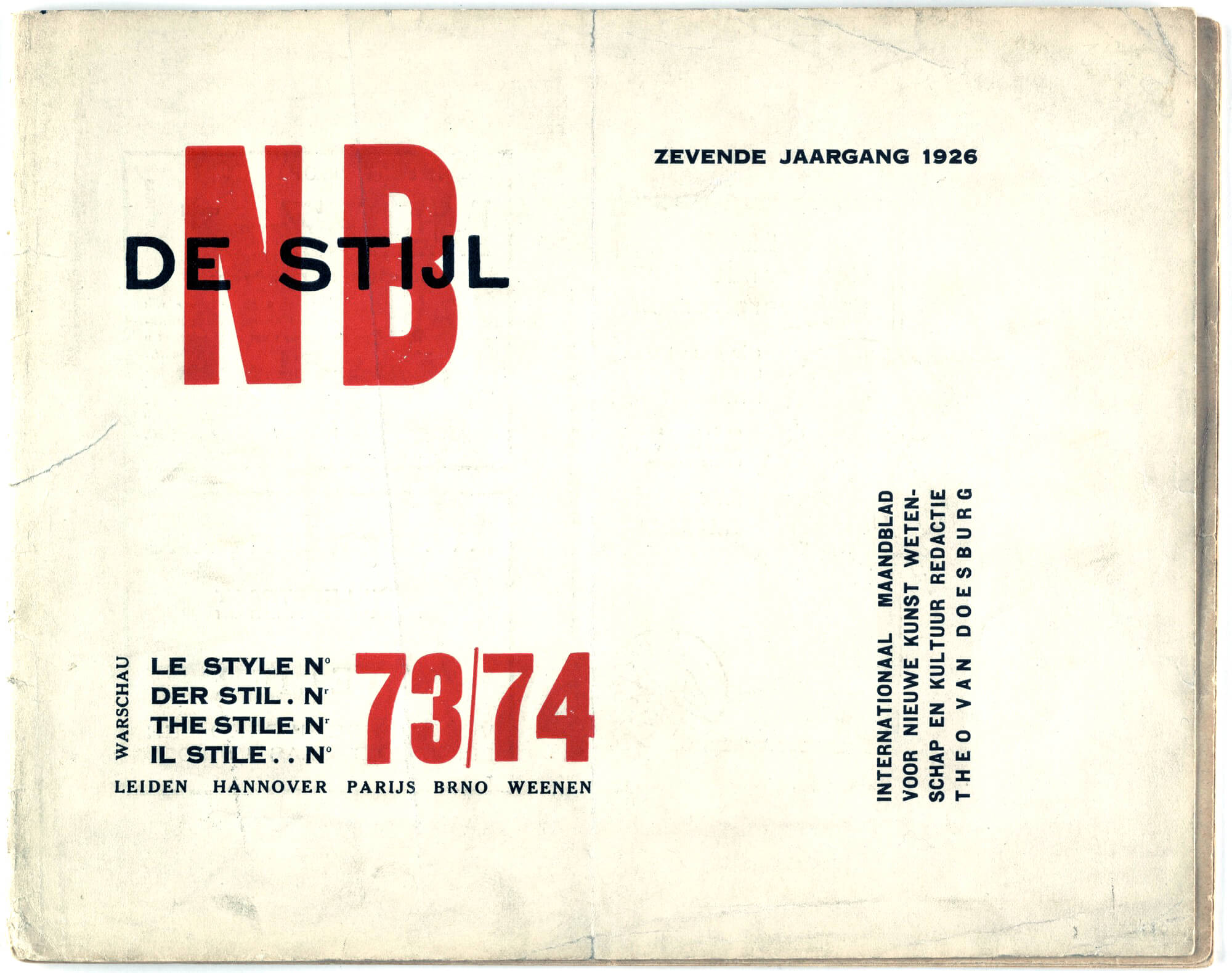

In 1922 the Bauhaus was accused of unproductivity and superficiality in an article by Vilmos Huszar which appeared in the September issue of De Stijl. De Stijl was a publication issued by Theo van Doesburg who himself worked at the Bauhuas but spoke very critically about its direction. During his lectures in Weimar, Doesburg would scream at students about Constrctivism whilst his wife Nelly played disharmonies on her piano. He used to accuse students as “Romantics”.

In time, following De Stijl course he had organised, Doesburg set up a De Stijl branch at the Bauhuas. Opposed to Gropius’s original idea, the school had become a formal institution where art was taught in straight lines and primary colours. As with De Stijl itself, it emphasised theory and suggested an effort to combine these theories into furniture design, painting and typography. With main exponents being Van Doesburg himself, Piet Mondrian and Gerrand Rietvelt, De Stijl idealised an art made of available materials and coloured in a constrained palette of primary colours, black and white.

The 1923-1925 Bauhaus in Weimar was conditioned by a fragile economy. The school lacked proper facilities and adequate heating. Furthermore, factions of Weimar’s business community, considered it as a threat to their existence. This instilled its main protagonists to work around rational and scientific idealisms but at the same time, demoralised many students. Gropius hoped students could start up a community and eventually collaborate.

The final years of the Bauhaus saw one last move to Berlin in 1932. Now with Mies van der Rohe at the helm, the school had changed into a very institutionalised structure where students’ opinion was given little or no importance. Only students from upper classes made it to the courses and workshops were made to use exclusive materials. This, and political turbulences in Germany led to the bitter end of the Bauhaus.