What follows is an extract of the aims that led for the completion of the 2014 Master research: “Art as a political choreography through social media: An investigation of social media as a tool and space for art to drive social narratives. The whole document can be accessed through Academia.com here.

The objective of this research is to explore and investigate how art can be envisaged as a driver of social narratives through social media in a bid to trigger and sustain the development of contemporary activism. Whilst web-based Social Networking Sites (SNSs) are generally associated with the sharing and diffusion of information amongst users and their networks, they also provide for a differentiated and customised usage of tools that lie within.

As Danah M.Boyd and Nicole B.Ellison claim: the cultures that emerge around SNSs are varied. Most sites support the maintenance of pre-existing social networks, but others help strangers connect based on shared interests, political views, or activities. Some sites cater to diverse audiences, while others attract people based on common language or shared racial, sexual, religious, or nationality based identities. (Boyd & Ellison, 2007, p. 1)

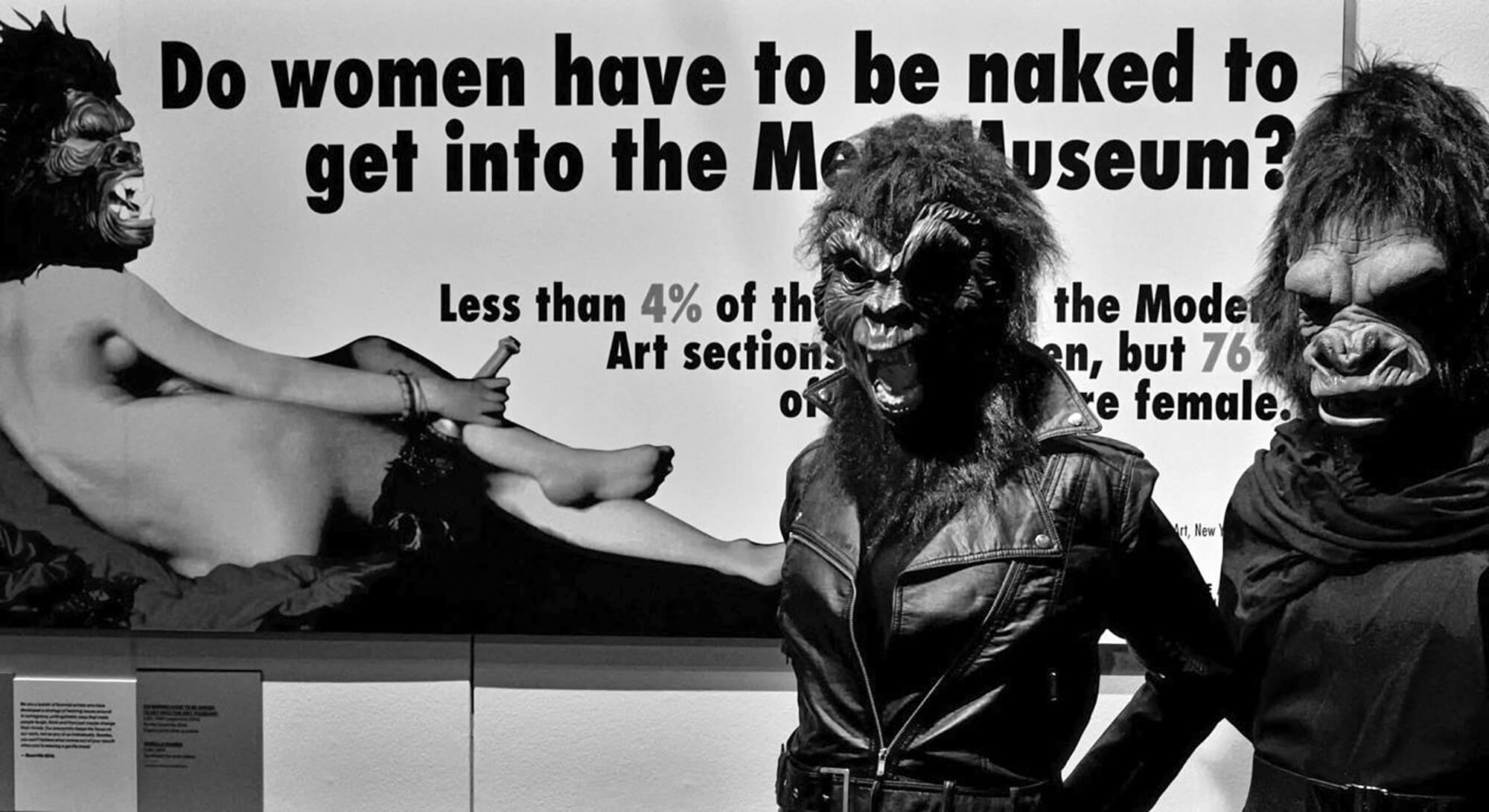

This study discusses and explores the role that an artistic intervention in digital art could play within collective activism. What can an artistic intervention contribute to the capitalist narratives of social media to regurgitate it into new forms of collective activism? Special attention is given to research and observations by researcher in new media and culture in contemporary global activism Dr Paolo Gerbaudo, in his book Tweets and the Streets– social media and Contemporary Activism (2012).

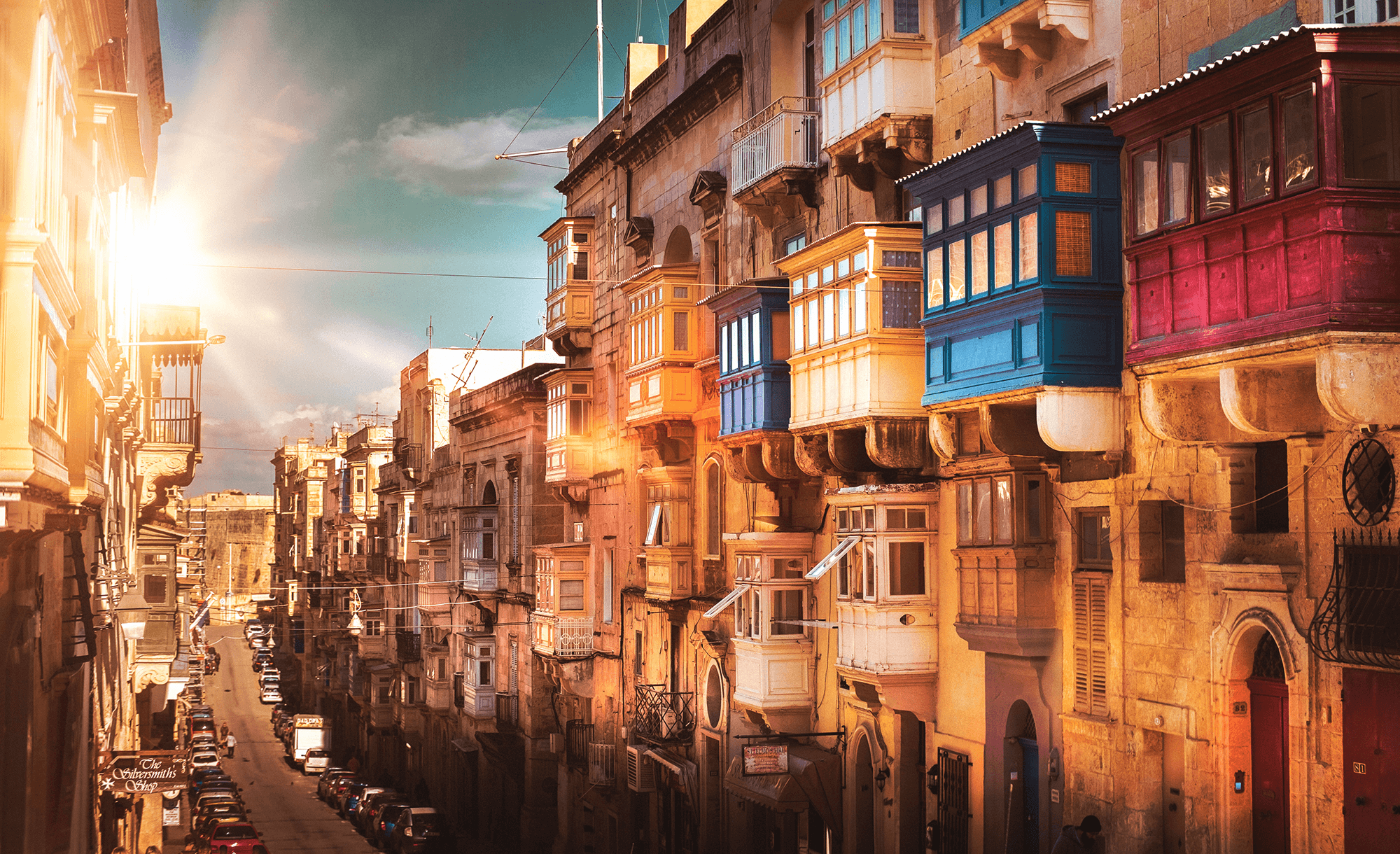

My two-fold project consists of an art installation that makes use of a custom social networking platform and incorporated mobile technologies, and discusses public participation in the generation of a social narrative. This narrative is displayed, in real-time, on a physical, digital screen to fuel further real-time interaction with the audience. The culmination of the project will be an artwork that represents this interactive process in the form of relational aesthetics – that which Bourriaud (2002) describes as “an art form where the substrate is formed by inter-subjectivity, and which takes being-together as a central theme, the “encounter” between beholder and picture, and the collective elaboration of meaning.” (p.14)

It aims at assisting and mediating for a “choreography of assembly” (Gerbaudo, 2012 p. 12) to take place in public spaces and thus, for art not to be disconnected from life. As hinted in the introduction, interactive participation might not be considered complete if there is a missing transmission or reception end to a communication. Twining (1980) claims that alienation happens “if man interprets or experiences this interaction as destructive, in terms of a loss of control or an emerging negative definition of self, the alienation process is initiated and self-estrangement is the potential outcome.” (Twining, 1980, p. 422).

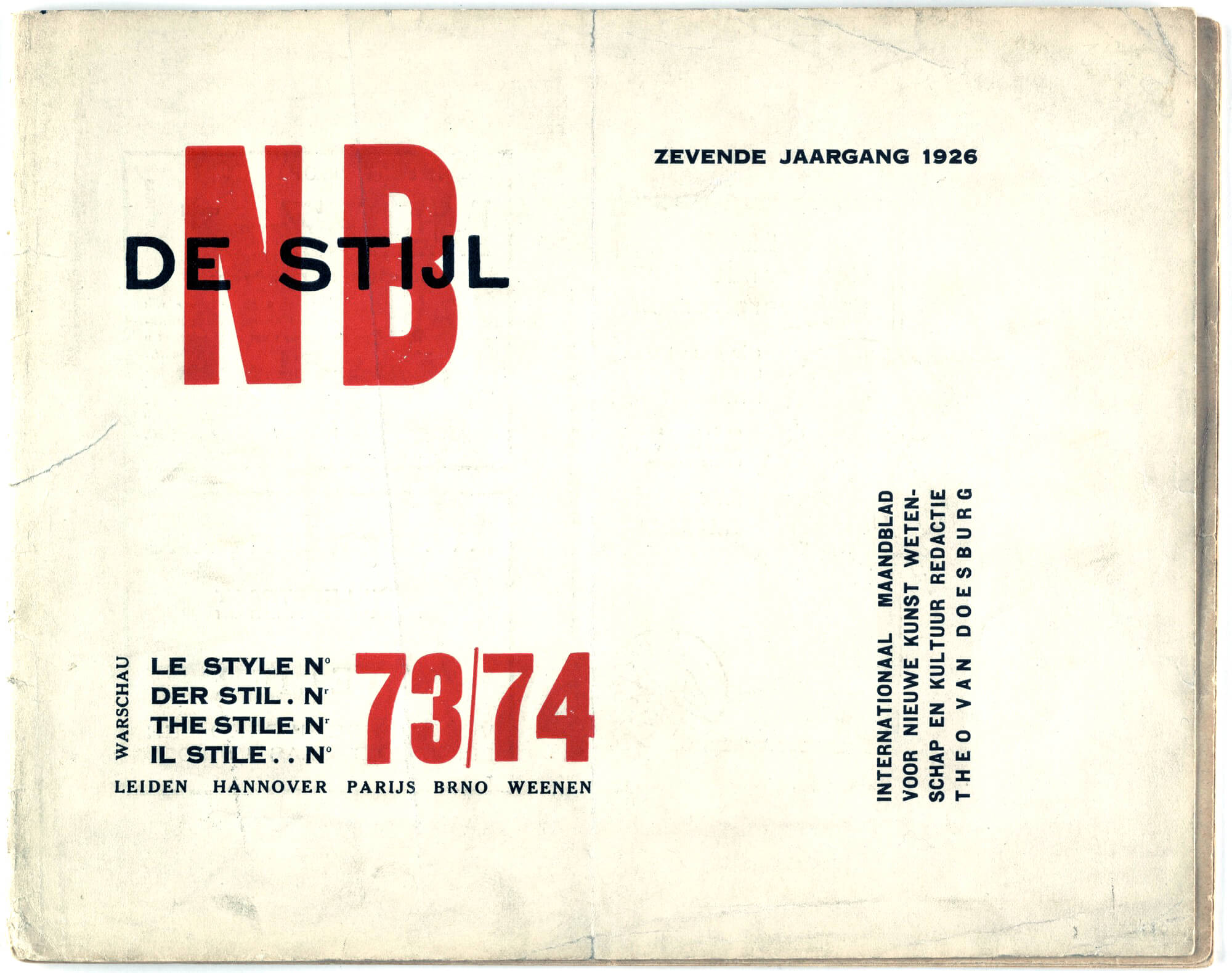

All along the way, social media aimed at replicating the effect of the ‘old’ newspaper and poster movements and motivate people into new relations. Yet, some argue, they might have peculiarly contributed to further distancing. That is where art can play its distinctive role in the “remaking of the experience of the community in the direction of greater order and unity” (Dewey, 1980, p. 81). This would be a role of mediation between alienation and activism.